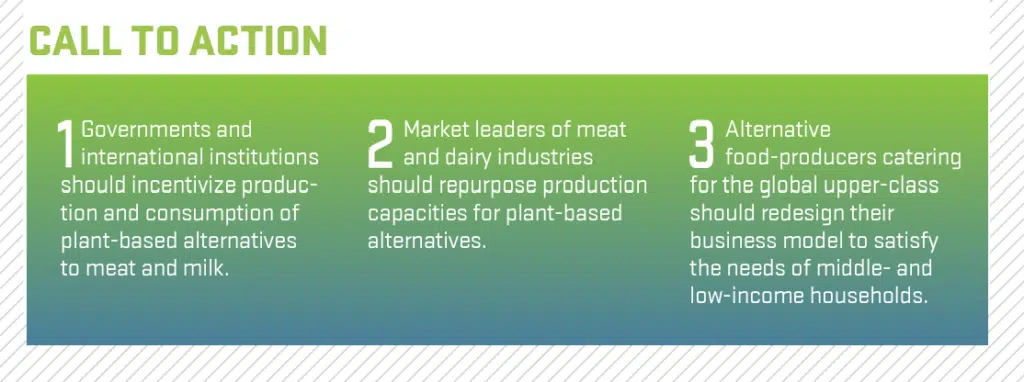

The issue at stake: With skyrocketing food prices, the livelihood of billions of people is at risk. Plant-based alternatives to meat and milk can increase food security by decreasing livestock feed. The time is ripe for massive upscaling of meat and milk alternatives – and an equally massive downscaling of prices.

The already high prices for ess ential foodstuffs like wheat or corn have risen even faster in the first months of 2022. The world is facing a huge shortage of grain, and the supply is not likely to recover in the short term. The probable result: The livelihood of billions of people will suffer, hundreds of millions of people will even face problems to put the daily bread on the table. And without food security, the cohesion of societies is at risk. One of the best ways to increase grain supply is the decrease of livestock. For each calorie of beef, seven calories of fodder are needed, for chicken the relation is 1 : 2. So the less cattle or chicken have to be fed, the more grain is left for human consumption. This is especially the case for those high-income countries which consume three times more meat than the global average. Less burgers in Europe can lead to cheaper bread in Africa. Sure, meat, milk and cheese are rich in protein, and protein is needed for a healthy diet. But in the latest years, a lot of alternative protein sources have been developed: plant-based milk, veggie burgers or vegan cheese. They resemble the animal-based products in look, feel and taste, but their production needs much less resources: less water, less energy, less grain. They are climate-friendly, they are animal-friendly and they could come handy as remedy against global food shortage.

There’s a catch, though: Plant-based meat or milk are more expensive than their animal-based competitors, often double the price or even more. Recommending soy milk instead of dairy milk sounds a bit like recommending to eat cake, when you can’t afford bread. But there’s only one reason for these high prices: Most of the plant-based alternatives are marketed to a small niche of green cosmopolitans, that are willing to pay a premium price for their good conscience. Though, honestly, they can be produced much cheaper than dairy or meat products. Oat milk for example is mainly some oat flakes soaked in water, a drop of oil added, blended, ready. So, one of the best remedies against the global food shortage has been parked in an upper-class niche market, shying away from the mass market with its lower profit margins, but higher impact on humanity. But in times of rising food insecurity, a turnaround is needed. The time is ripe for massive upscaling of meat and milk alternatives – and an equally massive downscaling of prices. History knows two ways to achieve a turnaround from niche to mass markets: private and public. Private like Henry Ford’s disruption of the car industry. In 1913, he switched his business model from expensive niche markets to cheap mass production; the rest of the industry had to follow. Or public like the promotion of the potato by Prussians king Frederick the Great around the year 1760. He gave multiple orders to the Prussian farmers to cultivate the new, highly nutritious crop, earning him the nickname “potato king”. So: Who wants to become the “Henry Ford of veggie burgers” – or the “soy milk president”?